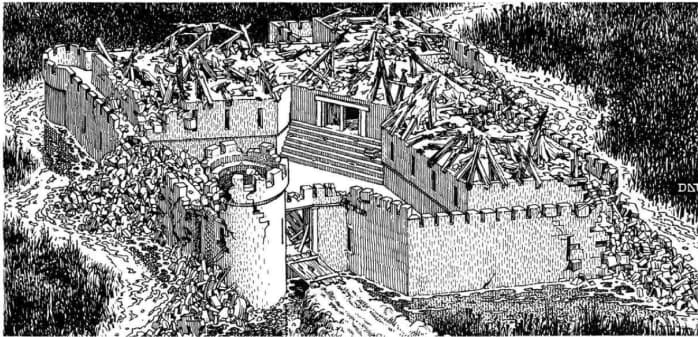

I run an AD&D 1e game for some close friends and family, none of whom had ever roleplayed before. (Now they’ve been at it for year, and have reached level 3, so I guess they aren’t quite “brand new” to the hobby, but they still have trouble with the actual rules.) I’m currently running T1 Village of Hommlet. One of the characters, Whiff, had climbed atop the exterior wall of the moathouse, which looks like this:

His player, Arbor, wanted him to jog along the crenelations and check out the perimeter of the old fort. A good plan.

As the party was separated, I rolled random encounter checks for both groups (the main body of the party, and Whiff) simultaneously. Whiff had the misfortune of encountering a giant tick at 30 feet with surprise. I decided that the tick must be on the wall as well, and in front of Whiff, or else no encounter would even happen. (Whiff was much faster than the tick, and Arbor knew the tick had no treasure, so they wouldn’t have even had to make any tactical choice: they would have just said, “Ok, I keep going and ignore the tick”. In which case, why did I bother rolling?) So Whiff had to kill the tick, get over or around it, or turn back and flee from it.

The tick moved on its one segment of surprise, not even reaching Whiff. Whiff won the next initiative round. Another player, Dean, urged Arbor to kick the tick off the rooftop. “Ok,” I said, “Make a normal attack roll, and if you hit, then instead of doing damage you kick the tick off the roof.”

Dean was shocked. “What do you mean? Can’t he just do it?”

I explained that I didn’t think he could. The tick had an AC of 3 (if I recall correctly) and 15 HP. One combat round is a full minute long. In that time, you’re already trying everything you can to hurt the tick, including kicking it. Its low AC and high HP are abstractions telling us in general how hard it is to defeat it, not just how thick its skin is and how many “meat points” it has. But, if a character wants to give up their chance of damaging an enemy, and focus all their efforts on one particular action (“stunting”), they can. But it’s not automatic. The game already tells us how hard it is to defeat the tick, with its AC and HP. Stunting bypasses the HP, but not the AC – that’s double-dipping.

He was not really convinced, but he went along with it. We haven’t talked about it since.

I think there are plenty of different reasonable reactions a different referee could have had here. I even think “Ok, you kick it off!” is a reasonable reaction, as long as it’s applied consistently. (But this would be pretty punishing if it were applied consistently – I doubt the players would want to be kicked off of ledges willy-nilly themselves.)

I was struck, in this example, by the depth of the misunderstanding here. We’d been picturing the relationship between the rules and the in-game actions totally differently. I still don’t think Dean has come over to my side.

I’m curious how you would have handled this misunderstanding/disagreement, when such things have arisen in your games, how you might have explained my point of view (as you understand it) differently, and all the rest.