In my intro post I wrote that running my game A Viricorne Guide recently restored my faith in my design instincts after designing and playtesting a couple of other games that never came together as fun as I wanted them to be.

A Viricorne Guide in contrast was just fun and so easy for me to run. It’s intended as a one shot. Your characters are only allowed to stay in Viricorne for a short time. Afterwards I wished I could run it for more sessions. I’ve been thinking a lot about why it was so fun/easy for me.

I wrote it in 2019 for the #RPGenesis jam, 5000 words in a week, mechanical design plus writing and graphics and layout. There wasn’t a lot of time for me to overthink anything.

Player characters are traditional RPG adventurers who probably have killed other beings where they live and taken their stuff. And actually my vision for the game was that a group would play it as an interlude to their D&D or Pathfinder or Savage Worlds or traditional fantasy whatever RPG with those same characters, but with A Viricorne Guide’s own resolution mechanics.

I wrote in the voice of the guide, Sholor, the player adventurers hire for their time in Viricorne. It’s all stuff like:

“And what brings you to the Reborn City? You’ve come as a group, so likely you’re here to pay a fine for crimes committed as adventurers? You’ve murdered creatures protected by the Treaty of Manlikes? And you’ve taken their stuff? You will need help to find a Judge who will take your payment, and not curse you. Or perhaps it’s something else? You’ve inherited property you need to claim? You have a venereal disease and need a healer who is not a quack? You have been hired for some purpose and are here to meet your employer?”

And:

“Notice my tattoos. It’s how you know you’ve hired the best guide, because I have the most. I can take you anywhere with my tattoos, because I have payed all the protection rackets. This one is so I can take you to the best prostitutes. This one is so we can even use the Corne of Transformation — or you can, I am already perfected.”

And:

“In the food plaza, notice how some people have blue soot smeared on their lips? You can’t just purchase food from the sellers. You have to help. If a seller sees you without the soot, they’ll give you work to do. A series of several tasks probably. Cut some mushrooms. Carry some broth. Tend a fire. In the morning perhaps, help load a smoker. Filet some fish. Wash some trenchers. Harvest needed spices from one of the roof gardens around the plaza. Serve completed food to a customer. And when you’ve done your work to their satisfaction they’ll reach into their firepit for the blue soot and smear it on your lips — it’s from special coals they use in the fires — and then they or any other seller know you’re cleared to buy food, and the soot wears off when you eat. The tradition of doing some small work creates a wonderful, shared experience of human connection.”

And I don’t know, it all just worked.

The characters arriving by climbing the Touch-and-Go up the side of the rock face to Viricorne made it easy to presume they were hungry/thirsty. We all just knew they would be without discussing it. Then, the way the food market works, so they had to do tasks before they could buy food, made it easy to get them interacting with people. And it was so easy to just have people ask, “What brings you to Viricorne?” or “Did you have a nice day in Viricorne?” The context of Viricorne being a city that always had lots of visiting outsiders made that easy. It made starting conversations easy. It felt so natural, and it helped us get to know their characters.

And whenever I needed a bit of description, about the Corne of Patience, or Onsen Raba, or whatever, it was there in the text for me to read if I wanted, in Sholor’s voice, or to quickly summarize in my own voice.

That’s my natural style of running NPCs. Sometimes in their voice. “Tell me why you would leave your ancestral city for a dangerous life as an adventurer?” And sometimes in third person. “He asks about where you grew up.” I’m not sure how I decide. It’s a gut decision.

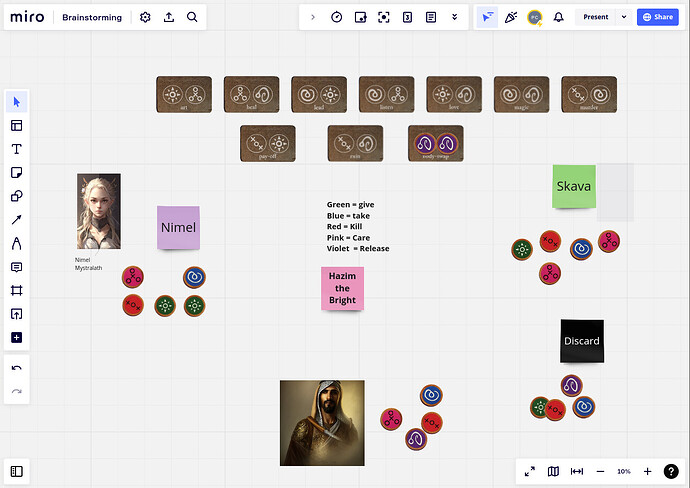

And the mechanics of sometimes needing a specific token to be contributed by another player made for lots of player investment in each other. When you help pay for someone’s outcome it can affect your character too:

“Ruin costs Kill and Release. It’s using your own power and judgement to negate an aspect of someone, or to end an institution. You’re tearing something down in hopes of something replacing it that suits you better. If you pay for it with both tokens yourself, then in the future you can do it again using any of your tokens you want, as if they were Kill and Release tokens. If another player paid one of the tokens for your act of Ruin, then both of you put any remaining Kill tokens you may have in the discard pool.”

I’m not active in Adept Play, but two of the players are, and the third is the partner of one of those two, and I know Ron pretty well from years ago. I know he’s big lately into the importance of players “knowing how to play”. You can make an incoherent stat+skill game from the 80’s fun if the players know how to play. And I think definitely some of the fun of this session of A Viricorne Guide is because the players definitely know how to play.

But also I think the situation of arriving at Viricorne and its customs and the places in it made it easy for me to draw the players in. By the end of the game the characters had visited Onsen Raba and I’d put the plaque of Body-swap into play, and two players had swapped bodies and had fun, really emotional interactions with NPCs. They took really emotional risks with their characters. I loved it.