Consider the following thought experiment or scenario. The goal is to explore the play technique or design space around a player’s role when observing or interacting with a scene in progress.

…

A thin crescent moon hangs sickly pale over the ancient city of Umma Sabikh.

The SULTAN sleeps soundly in a room atop the Royal Palace. The hangings by the window hardly stir in the heavy, thick air of midnight.

His youngest CONCUBINE lies sleepless at the foot of his bed, looking out at the moon and wondering about her past: how did she come to be here, in this ancient and dusty place?

Outside, scaling the wall in total silence, the Sumerian ASSASSIN has finally reached the top of the minaret and is but a short leap from the Sultan’s bedroom.

…

You are playing this game. One person is the Narrator, establishing the above description.

The SULTAN, CONCUBINE, and ASSASSIN could all be played by your friends, or maybe just one or two of them for now.

You, however, are simply watching and listening. You don’t have a character in the scene.

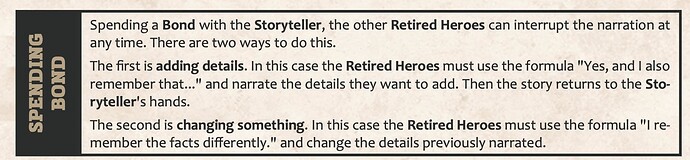

However, the game allows you a variety of clever (and sometimes subtle) ways to influence the events in play and the outcome of this scene.

Which do you choose, and what does it look like?

Tell us, in as much detail as you can.

…

The goal of this thread is to explore the design space available for players who don’t have a character present in the scene. What new modes of interaction, game mechanics, or special arrangements of the game can we come up with?

What do you wish you could do, in a game situation like this? What do you wish your fellow players could do while you’re playing out a scene?

It can be narrative, social, or mechanical.

(This post was a thought experiment I posted before once on Story Games and then at the Gauntlet - link to archive and the original archive. Let’s now see what ideas this community has to share. If you find it confusing, click through and see how people responded there and then! But I’d prefer your immediate and unbiased reaction or ideas.)